Proposed National Programs to Honor Abolitionists and Antislavery Activists

|

|

Introduction

Slavery began in British North America in 1619.

Movements to limit or end slavery began in the earliest days of British colonial America and the founding of the American republic.

Anti-slavery activities took numerous forms from the late 1600s through the end of the American Civil War. Ultimately, abolitionists and anti-slavery activists inspired and moved the country toward passing the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, ending slavery forever.

The first abolitionist organization, the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage, was established in Philadelphia in 1775.

Framers of the Declaration of Independence and, later, the Constitution of the United States, debated the issue of slavery. Many of the founding fathers wanted to exclude slavery from the new republic. Among them were John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, Benjamin Rush, and others. They believed that slavery was morally wrong and contrary to the ideals of the new republic. These ideals were equality and liberty.

After the American revolution, abolitionist societies were established in Massachusetts, Connecticut and New York. The leaders of these organizations were among the most prominent Americans of the time. They believed that slavery could be ended gradually, with compensation to the slaveholders.

As a result of the lobbying of these societies, states in New England began to legislate slavery out of existence. Among them were Pennsylvania, Connecticut and New York. Other states soon followed.

Before the federal Constitutional Convention met in 1787, six of the original states began legislation toward the complete emancipation of slaves. They were Vermont (1777), Massachusetts (1780), Pennsylvania (1780), Connecticut (1784), New Hampshire (1784), and Rhode Island (1784).

In 1794, New York began the legislative process, and in 1804, New Jersey adopted a plan for the gradual emancipation of slaves.

In 1787, the U.S. Constitution adopted a plan to abolish the foreign and domestic slave trade and, ultimately, to keep slavery out of all of the territories. A new federal law, authorized by Rufus King, would prohibit slavery in the following states: Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Iowa. These states would be admitted to the Union as free states.

In the early 1800s, attempts to end slavery entered a new era. Gradual emancipation was replaced with the idea of sending freed African Americans back to Africa. This was known as “colonization.” The American Colonization Society, was created in 1819. During this period, colonization societies were created throughout the south. Many thought that slavery would eventually would wither away. Some colonizationists believed that slavery was wrong. Others wanted to remove all Blacks from the south. By the late 1820s, the anti-slavery movement shifted from the south to the northern states.

By the 1830s, a new generation of abolitionists emerged. Inspired by their moral and religious ideals, they demanded an immediate end to slavery, and without compensation to slave owners. Abolitionists also called for freed enslaved peoples to be allowed into American society as equals.

From the 1830s through the 1860s, abolition and anti-slavery became one of the most contentious issues in American politics and society. The issue of slavery deeply divided the country. Southern politicians and slaveholders began a campaign to defend the institution. It dominated American politics for more than three decades. The very fabric of American democracy, and even the existence of the republic, was jeopardized by slavery.

Abolitionists and anti-slavery activists were a very small group. They represented only a small fraction of the US population. Nonetheless, they had a large influence on the political discussion of the day.

These abolitionists called for the ending of what was called the “peculiar institution” of slavery. The first success of the anti-slavery leaders was the prohibition of the African slave trade in the United States in 1808. Later, they called for the ending of all interstate commerce in slavery and the prohibition of the extension of slavery into the new territories and states. They also demanded the repeal of the fugitive slave laws, which required the return of fugitive slaves to their owners.

Abolitionists’ ultimate goal was the absolute and unconditional ending of slavery in the United States. To this end, they steadily lobbied state legislatures and the US Congress to call for the immediate end to slavery.

Before the Civil War, abolitionist societies sprung up throughout the northern states. In 1831, the New England Anti-Slavery Society was organized. In 1833, a meeting was held in Philadelphia, where abolitionists from New York, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts met to establish a national organization, the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS). Soon, auxiliaries the AASS and other anti-slavery societies were organized throughout the eastern and western states. In 1835, the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society was created and soon the New York Anti-Slavery was established. Both state auxiliaries of the AASS. By the 1850s, more than 2,000 societies existed, with a membership of more than 200,000.

The abolitionist movement was among the first times that Whites and Blacks worked together effectively toward major social and political reforms.

Abolitionists employed numerous tactics to accomplish their goals. They published pamphlets, tracts and articles, and they established dozens of abolitionist newspapers. They hired speakers to lecture on the topic, and hundreds of inspired individuals crisscrossed the country, spreading the message. They continued to lobby Congress and local legislatures.

Abolitionist leaders were often highly educated men. Many of them had intense religious feelings and commitments. Many were clergymen and elders of Protestant evangelical churches. Most of them traced their families to New England.

As the influence of abolitionists grew, southerners sought to diminish their effectiveness. They called for a ban on mailing anti-slavery tracts. In Congress, southern lawmakers put a “gag order” on petitions submitted to debate the issue of slavery.

After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, northern abolitionists created vigilance committees. These committees protected escaped slaves from being recaptured and returned to the south and defended them in court.

Abolitionists opposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which sought to determine if Kansas would become a slave state by popular sovereignty. It would allow new settlers to determine the question of slavery in the new territory.

Many abolitionists aided slaves in the Underground Railroad. They helped thousands of slaves to escape from the South and relocate to the North and took them to freedom in Canada.

The abolitionist movement was not popular, and was supported by few people in the north. The northern economy depended on the products of slavery. Cotton, tobacco, sugar and other commodities were creating great wealth in New England.

Abolitionists were often seen as fanatics. They were accused of driving a wedge between the north and the south, disrupting the economies of both regions. They were frequently ridiculed and were objects of contempt.

Abolitionists paid a heavy price for their beliefs. Some were jailed for their activities, and several died in custody. Attempts to silence them were often violent. A number of abolitionists were beaten. Several abolitionists were killed by angry mobs.

Who were the abolitionists and anti-slavery activists? They were both White and African American. Abolitionists came from all walks of life, classes, professions, and religious beliefs.

The work of these individuals and organizations made it possible for Abraham Lincoln to abolish slavery on January 1, 1863, when he signed the Emancipation Proclamation. The Congress of the United States passed the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, ending slavery, on January 31, 1865. This act freed more than four million African Americans from slavery.

The abolitionist movement was one of the most important social movements in the history of the United States. Out of it grew the great Nineteenth Century reform movements, such as women’s rights and suffrage, Native American rights, temperance, prison and labor reform.

Abolitionists were inspired by the notion that slavery was morally and ethically wrong, and that it was an unjustifiable institution. Abolitionists were the conscience of the nation. They reminded us of the unfulfilled promises of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights.

Yet more than 150 years after leading the fight to end slavery, most of these abolitionists have been forgotten.

The purpose of this program is to honor those courageous men and women who fought for the rights of their countrymen.

We would like to take the opportunity to create a commemorative program to do so.

Return to Top of Page

Honoring American Abolitionists, Anti-Slavery Activists and Opponents of Slavery

We have researched and produced a list of more than 3,000 abolitionists, anti-slavery activists and opponents of slavery, as well as a list of more than 300 abolitionist organizations and their leaders and officers.

These lists consist of American abolitionists, anti-slavery activists and opponents of slavery. They were drawn from a number of primary and secondary sources, including prominent archives. They include African American and Caucasian abolitionists and anti-slavery activists.

This list is a work in progress. We intend to continue our research and add more names, as they are found. We will also be including biographical sketches of each of these individuals and additional references.

We are including in this list all anti-slavery activists and opponents of slavery, whatever their motives, whether humanitarian, economic or political. Some of these individuals were against slavery in principle, on moral grounds, while they possessed and exploited slaves themselves. We are also including individuals regardless of their orientation toward the ending of slavery. Among the abolitionists, we are including those whose methods were ultra-radical, radical, immediatist, moderate and gradualist.

It is our hope to have these individuals in a comprehensive reference work so that their actions can be documented and that their work can be recognized.

This list will be read at future commemorative programs honoring opponents of slavery.

This list was initially read at the Antietam national historic battlefield site on the 150th anniversary of Lincoln’s announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation. This was the first time the names of abolitionists was read publicly in any ceremony, to our knowledge. The list was read by students, faculty and other invited members of the program.

The programs were sponsored by West Virginia University President’s Office of Social Justice, the Center for Black History and Culture, and the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences.

We also did a reading of abolitionist names at the African Burial Ground National Historic Site in New York City in 2013.

An additional name-reading event was held in Savannah, George, in 2015 by the Center for Jubilee, Reconciliation and Healing, Inc., Patt Gilliard-Gunn, President.

Examples of abolitionist groups are:

- American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS), founded in New York City, December 1833, disbanded 1870; published The Emancipator and The Anti-Slavery Standard; had 1,350 affiliated societies and 250,000 members in 1838. By 1840, there were 2,000 affiliated societies.

- American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society (A&FASS), founded 1840 by Arthur and Lewis Tappan.

- Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society (BFASS), formed October 1833 (1832?), disbanded 1840; newsletter, The Liberty Bell. Associated with the American Anti-Slavery Society and the New England Anti-Slavery Society. Had African American and White members. Represented Evangelical Christian, Baptist, Presbyterian, Congregational and liberal denominations, including Quaker and Unitarian. Founded by Anne Chapman, Caroline Weston Chapman, Deborah Chapman and Maria Weston Chapman.

- New England Anti-Slavery Society (NEASS), founded January 1832, Boston, Massachusetts. Founded and led by William Lloyd Garrison, Arnold Buffum, Elizabeth Buffum Chase and David Lee Child.

- New York State Anti-Slavery Society (NYSASS), headquartered in Utica, New York, founded Fall 1835, newspaper: Friend of Man. Founded and led by Alvan Stewart, William Jay, William Goodell, Myron Holley, Gerrit Smith and Beriah Green.

- Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, and the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, founded 1789. Quaker abolitionist organization whose leaders were almost all Hicksites. They promoted a moderate approach to ending slavery in the United States. By the late 1830s, it supported education for Black children, hiring lawyers to prevent or thwart kidnapping by slave catchers, and to aid fugitive Blacks in the court system. Founded and led by Dr. Benjamin Rush.

Examples of abolitionists and anti-slavery activists to be honored are:

- political leaders and statesmen

- political and social reformers

- members of the diplomatic corps

- clergymen and religious leaders

- members of the Underground Railroad

- escaped and former slaves who publicized the evils of slavery

Return to Top of Page

Proposed Programs

We propose several programs to commemorate and honor American abolitionists and anti-slavery activists. They are:

- Create a historic database of abolitionists and anti-slavery activists and organizations. This to be posted as a website and a possible publication.

- Create a U.S. commemorative day designated as Abolitionists and Anti-Slavery Activists Day.

Return to Top of Page

Commemorative Reading of the Names of Abolitionists and Anti-Slavery Activists

We propose to create an ongoing program to read the names of anti-slavery activists at colleges, universities, historic sites and places that relate to civil rights and human rights issues.

Some of the places that we propose where an annual reading of the names could take place are:

- Lincoln Memorial

- Emancipation Hall, Visitor’s Center, U.S. Capitol

- Frederick Douglass National Historic Site

- State capitols

- National Park Service has a list of sites that are called Sites of Conscience.

- Martin Luther King Memorial, Washington, DC

- National Civil Rights Museum, Memphis, Tennessee

- Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

- Women’s Rights National Historic Park, Seneca Falls, New York

- Historically Black Colleges and Universities, including Fisk University, Howard University, Morehouse College, Wilberforce University, and others; also to be included are colleges that promoted civil rights and the admission of African American students, for example Oberlin College

- National Susan B. Anthony Museum and House, Rochester, New YorkWe propose that students, faculty, community leaders, and other interested members of the community should participate in these programs to read the names of abolitionists. At these programs, the names of all abolitionists and anti-slavery activists would be read in alphabetical order. The reading would take approximately four hours.

Return to Top of Page

Historic Database of Abolitionists and Anti-Slavery Activists

We have created a comprehensive database of abolitionists and anti-slavery activists. This list includes the names of the prominent individuals who were involved in ending slavery in America.

According to several historians, there were thousands of individuals involved in opposing and ending slavery. There are numerous books and reference materials that has been drawn upon to create this list. In addition, there are many archives containing the letters, diaries of abolitionists and anti-slavery activists that are being researched.

As previously stated, we have created a database of 3,000 names and more than 300 organizations. We have produced, as stated previously, an illustrated list of prominent abolitionists and anti-slavery activists.

This material has been posted on this website.

We have posted an online encyclopedia of slavery and abolition. The entries include biographies of abolitionists and their organization. These include a number of contemporary histories of abolition.

Return to Top of Page

Create a U.S. Commemorative Day

We propose to create a U.S. commemorative day designated as Abolitionists and Anti-Slavery Activists Day. The proposed date could be any of the following:

- September 22, to coincide with Lincoln’s announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation after the battle of Antietam, on September 22, 1862.

- The last Friday in June, which would coincide with the proposed holiday, proposed by African American groups after the Civil War.

- January 1, to coincide with the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation at the White House by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863.

This would entail lobbying members of Congress to enact legislation to create the holiday. It would not be a legal holiday, but a day similar to Flag Day, Father’s Day or Mother’s Day. We would work with the Congressional Black Caucas and other Members of Congress who would have a special interest in this day. Note: At least one State has designated September 22 to commemorate the Emancipation Proclamation.

Return to Top of Page

Congressional Gold Medal

We propose to lobby Members of Congress to pass a bill to have Congress issue a Congressional Gold Medal honoring and commemorating abolitionists and anti-slavery activists.

The U.S. Congressional website (http://history.house.gov/Institution/Gold-Medal/Gold-Medal-Recipients/) describes the Congressional Gold Medal: “Since the American Revolution, Congress has commissioned gold medals as its highest expression of national appreciation for distinguished achievements and contributions. Each medal honors a particular individual, institution, or event. Although the first recipients included citizens who participated in the American Revolution, the War of 1812 and the Mexican War, Congress broadened the scope of the medal to include actors, authors, entertainers, musicians, pioneers in aeronautics and space, explorers, lifesavers, notables in science and medicine, athletes, humanitarians, public servants, and foreign recipients.”

Some prominent groups that have received the Congressional Gold Medal are:

- Little Rock Nine awarded October 21, 1998

- Navajo Code Talkers awarded December 21, 2000

- The Tuskegee Airmen awarded April 11, 2006

- Women Airforce Service Pilots of WWII (‘WASP’) awarded July 1, 2009

- 100th Infantry Battalion and 442nd Regimental Combat Team, and the Military Intelligence Service, United States Army awarded October 5, 2010

Return to Top of Page

Commemorative US Postage Stamp

We would apply to do a commemorative US postage stamp, or a series of US postage stamps, to honor prominent anti-slavery activists and abolitionists. This could be similar to the block of stamps that was issued in 1995 honoring prominent individuals from the Civil War.

Return to Top of Page

Tree Planting

We propose to plant a memorial grove of trees in an appropriate location in honor of the many abolitionists who worked to end slavery. Perhaps it could be in our nation’s capitol.

Some of the trees could be dedicated specifically to the memory of individual abolitionists and anti-slavery activists.

This would be similar to a tree planting at the Holocaust museum in Jerusalem that is called the Forest of the Righteous. This is on the Mount of Remembrance, also next to the Israeli National Cemetery. There is a forest of more than 10,000 trees planted in the memory of individuals who rescued Jews during the Holocaust.

Return to Top of Page

Conclusion

This will be the first annual program to honor American abolitionists, anti-slavery activists and opponents of slavery on the September 22 anniversary of Lincoln’s announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation.

In addition, we are hoping that the reading of the names may be established at Civil War national battlefield sites and at university and college campuses on an annual basis. |

|

|

|

Return to Top of Page

Leaders and Prominent Abolitionists, Anti-Slavery Activists and Opponents of Slavery

This is a sampling of some of the leading abolitionists, anti-slavery activists and opponents of slavery who will be honored in this program. These individuals are from all walks of life and all occupations. They represent both Caucasian and African Americans. Among them are political leaders, newspaper editors, artists, poets, writers, businessmen, and philanthropists. Please click here for a complete illustrated list.

|

|

|

|

|

|

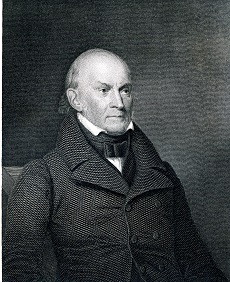

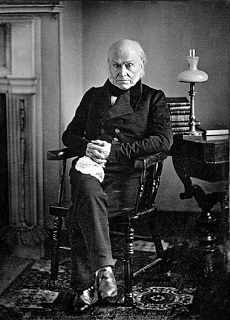

ADAMS, John Quincy, 1767-1848, Massachusetts, sixth U.S. President (1825-1829), U.S. Congressman (1831-1848), U.S. Secretary of State, lawyer, anti-slavery political leader, activist, son of second U.S. President John Adams. Opposed the Missouri Compromise of 1819, which allowed the expansion of slavery in southern states. Adams presented 693 anti-slavery petitions to the House of Representatives. Fought against the “Gag Rule” in Congress, which prevented discussion of the issue of slavery in the U.S. House of Representatives. The Gag Rule was revoked in 1844. Opposed the annexation of Texas and the extension of slavery to new territories. Opposed slavery in the District of Columbia. Counsel for the defense of slaves in the Amistad case. In 1841, he argued for the freedom of the slaves on the Amistad ship before the U.S. Supreme Court. He won the case and secured their freedom. Adams declared “that freedom is the natural right of man, and that by the laws of nature, and of nature’s God, an immortal soul cannot be made chattel.” Also stated, “It is among the evils of slavery that it taints the very sources of moral principle. It establishes false estimates of virtue and vice; for what can be more false and heartless than this doctrine, which makes the first and holiest rights of humanity to depend upon the color of the skin?” |

|

ANTHONY, Susan Brownell, 1820-1906, reformer, abolitionist, orator, leader of the female suffrage movement, radical egalitarian, temperance movement leader. Became active in the abolition movement in the mid-1850’s. Member of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Founded Women’s National Loyal League with Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 1863 to fight for cause of abolition, co-founded American Equal Rights Association (AERA) in 1866 to fight for universal suffrage. |

|

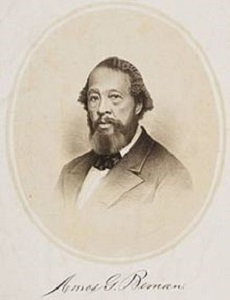

BEMAN, Amos Geary, 1812-1874, African American clergyman, abolitionist, speaker, temperance advocate, community leader. Member of the American Anti-Slavery Society 1833-1840. Later, founding member of the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. Traveled extensively and lectured on abolition. Leader, Negro Convention Movement. Founder and first Secretary of Anti-Slavery Union Missionary Society, later organized as the American Missionary Association (AMA), 1846. Championed Black civil rights. Promoted anti-slavery and African American civil rights causes. Worked with Frederick Douglass and wrote for his abolitionist newspaper, The North Star. |

|

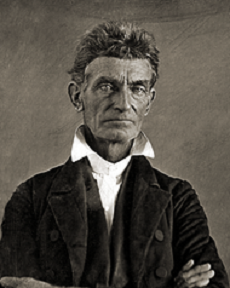

BROWN, John, 1800-1859, radical-militant abolitionist leader, wrote Provisional Constitution and Ordinances for the People of the United States (1858). Condemned slavery. In 1855, Brown went to Kansas during the struggle to determine whether it should be a free or slave state. With 23 volunteers, including five African Americans, Brown led a raid against the Federal Arsenal at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, on October 16, 1859. Three of his sons participated, Oliver, Owen and Watson, as well as brothers of his son-in-law, William and Dauphin Watson. He was captured, tried and convicted and was executed on December 2, 1859 along with four of his co-defendants. He was supported by six prominent abolitionists. They were Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Samuel Gridley Howe, Theodore Parker, Franklin B. Sanborn, Gerritt Smith, and George W. Stearns. They were known as the “Secret Six.” |

|

CHAPMAN, Maria Weston, 1806-1885, educator, writer, newspaper editor, prominent abolitionist leader, reformer. Advocate of immediate, uncompensated emancipation. Editor of the anti-slavery newspaper The Liberty Bell. Also helped to edit William Lloyd Garrison’s newspaper, the Liberator. Co-founded and edited the National Anti-Slavery Standard. Leader and founder of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society (BFASS), which she founded and organized with twelve other women, including three of her sisters. The Society worked to educate Boston’s African American community and to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia. In 1840, Chapman was elected to the executive committee of the American Anti-Slavery Society. She was Councillor of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society from 1841-1865. Her husband was prominent abolitionist Henry Grafton Chapman, with whom she co-edited The National Anti-Slavery Standard in New York. |

|

CORNISH, Reverend Samuel E., 1795-1858, free African American, New York City and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, abolitionist leader, clergyman, publisher, journalist. Published The Colonization Scheme Considered and its Rejection by Colored People and A Remonstrance Against the Abuse of Blacks, 1826. Cornish was co-editor of the Freedom’s Journal, the first African American newspaper. Editor, The Colored American, 1837-1839. Leader and founding member of the American Anti-Slavery Society. In 1840, joined the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society and served on the Executive Committee, 1840-1855. |

|

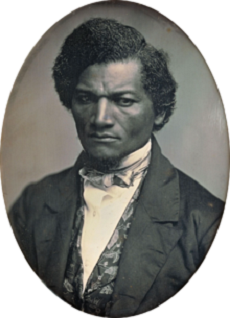

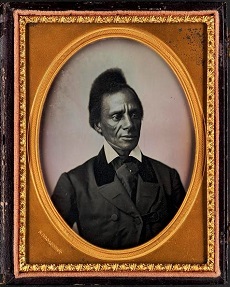

DOUGLASS, Frederick, 1817-1895, African American, escaped slave, author, diplomat, orator, radical abolitionist leader. Began his abolitionist career as an agent of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. Published and edited The North Star abolitionist newspaper in Rochester, New York, for 17 years. Wrote Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglas: An American Slave, in 1845. Also wrote My Bondage, My Freedom, 1855. Actively supported women’s rights and suffrage. Recruited soldiers for the African American regiments in the Union Army during the Civil War. During Reconstruction, Douglass worked for civil rights and suffrage for African American men. |

|

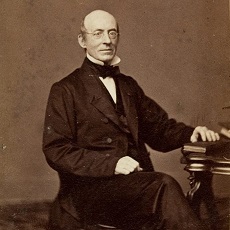

GARRISON, William Lloyd, 1805-1879, journalist, major abolitionist leader. Early in his career, he supported colonization and gradual emancipation. He later changed his views to adamantly oppose colonization. Co-founder of the American Anti-Slavery Society, December 1833, and the New England Anti-Slavery Society. Co-editor of anti-slavery newspaper, Genius of Universal Emancipation, in 1829. Supported cause of uncompensated immediate abolitionism. Viewed slavery as highly immoral and sinful. Promoted full citizenship and rights for African Americans. Founder, editor, The Liberator, weekly newspaper founded in 1831, published through December 1865. After the passage of the 13th Amendment, ending slavery, Garrison closed The Liberator and promoted the issues of women’s suffrage and rights for Native Americans. |

|

GIDDINGS, Joshua Reed, 1795-1865, statesman, U.S. Congressman, Whig from Ohio, elected in 1838. First abolitionist elected to House of Representatives. Worked with Congressman and former President John Quincy Adams to eliminate “gag rule,” which prohibited anti-slavery petitions from being submitted to Congress. He resigned from Congress after being censured for his stance against slavery. His district supported his policy, and Giddings was reelected to the U.S. House of Representatives, serving until 1859. He opposed Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and the further expansion of slavery into the new territories acquired after the Mexican War of 1846. In 1848, he left the Whig party and affiliated himself with the newly established anti-slavery Free Soil party. Giddings opposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. Leader and founder of the Republican Party. Argued that slavery in territories and District of Columbia was unlawful. Active in Underground Railroad. Giddings worked with other anti-slavery Congressmen forming an unofficial select committee on slavery. These representatives included: Seth M. Gates, Sherlock J. Andrews, and William Slade. Giddings supported Republican Presidential candidates John C. Frémont in 1856 and Abraham Lincoln in 1860. |

|

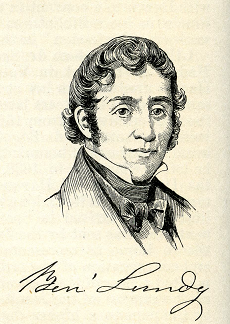

LUNDY, Benjamin, 1789-1839, philanthropist, Society of Friends, Quaker, radical abolitionist leader, anti-slavery author and editor. Lundy was one of the most important early abolitionists. Lundy was one of the first abolitionists to publish anti-slavery periodicals and give anti-slavery lectures. He was also among the first to create societies that would encourage people to buy products produced by free labor. He was a founding member and officer in the American Anti-Slavery Society. Organized the anti-slavery Union Humane Society, St. Clairsville, Ohio, in 1816, and wrote anti-slavery articles for the Philanthropist newspaper in Mount Pleasant, Ohio. In 1821, he founded and published the newspaper, Genius of Universal Emancipation, in Greenville, Tennessee. It was circulated in more than 21 states and territories, including slave states. He was a member of the Tennessee Manumission Society. In 1825, Lundy travelled to Haiti to negotiate with government officials to see if freed slaves in the United States could settle there. In August 1825, he founded the Maryland Anti-Slavery Society, which advocated for direct political action to end slavery. He lectured extensively and helped organize numerous anti-slavery groups in the Northeast. Lundy supported establishing colonies of freed slaves in Mexico. In the winter of 1829, he was badly beaten and almost killed by a slaveholder who accused him of libel. In 1836, published The National Enquirer and Constitutional Advocate of Universal Liberty, a weekly paper. In 1837, co-founded the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. In 1838, his property was destroyed by a fire set by a pro-slavery mob. |

|

REMOND, Charles Lenox, 1810-1873, orator, free African American. Agent for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. First Black abolitionist employed as spokesman in anti-slavery cause (in 1838). Member of the Executive Committee and Manager of the American Anti-Slavery Society, 1843-1853. Attended the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London in 1840. Lectured with Frederick Douglass on abolition. Recruited African American soldiers for the Union Army. |

|

TUBMAN, Harriet, 1822-1913, Maryland, African American, abolitionist, leader of the Underground Railroad, orator, Civil War Scout and nurse. Member of the Troy Vigilance Committee. Tubman was enslaved from her birth. After being threatened to be sold in 1849, she escaped to Philadelphia. She began her mission as a guide in the Underground Railroad in December 1850. In the 1850s, she made 19 trips through Maryland, aiding fugitive slaves escaping to the North and to Canada. She aided an estimated 300 fugitive slaves, none of whom was ever recaptured. She often worked alone in her rescue activities. Her success resulted in a $40,000 bounty on her head. She was an advisor to radical abolitionist John Brown. In the spring of 1862, she volunteered for the Union Army as a Scout and a spy, often travelling behind Confederate lines. After the war, she moved to Auburn, New York, and worked with older former slaves and orphans. She also worked to support freeman’s schools and worked for women’s right to vote. In 1897, she was awarded a pension of $20 a month by Congress for her wartime service. |

|

|

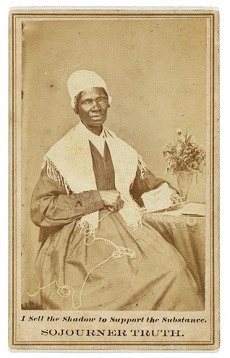

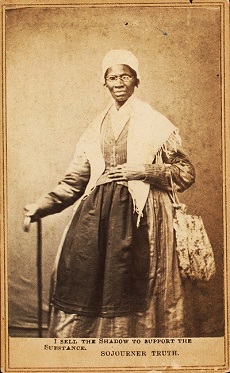

TRUTH, Sojourner (Isabella Baumfree), 1797?-1883, African American, anti-slavery activist, abolitionist, women’s rights activist. Truth, born as Isabella Baumfree, was born into slavery. She was treated harshly by her owner. Her father died of neglect. Two of her daughters, and all but one of her siblings, were taken away from her and sold. In 1827, she escaped with the aid of local Quakers. She was able to sue for the freedom of her son, Peter. This was one of the first cases of a Black woman successfully winning a suit against a White man. Around 1829, Truth moved to New York City. In 1843, she was inspired to rename herself Sojourner Truth. That year, she went on a religious mission, traveling through Long Island and Connecticut. Also that same year, she learned about the abolitionist movement. She became a member of the Northampton, Massachusetts, Association of Education and Industry, an egalitarian community. Through this community, she met abolitionist leader William Lloyd Garrison and African American abolitionist Frederick Douglass. She was so eloquent that abolitionist leaders sponsored her on a speaking tour. Beginning in 1850, she also began speaking at women’s rights conventions, becoming a leader in the women’s rights movement. Around 1850, she moved to Salem, Ohio. She used the offices of the Anti-Slavery Bugle as a center. She then traveled to Indiana, Kansas and Missouri. Wrote The Narrative of Sojourner Truth: A Northern Slave, 1850. She was able to sustain herself by selling copies of her slave narrative. She was attacked by pro-slavery advocates in Kansas and Missouri. By the mid-1850s, she traveled to Battle Creek, Michigan. During the Civil War, she recruited African American soldiers for the Union Army as well as working to see for their care. On October 29, 1864, Truth met President Abraham Lincoln in the White House. She stayed in Washington for two years, assisting freed slaves. In December 1864, she was appointed counselor for the National Freedman’s Relief Association. After the war, she protested the segregation of streetcars in Washington, DC. It was the first sit-in protest. In March 1870, she met President Ulysses S. Grant to petition the federal government to establish a state for freed slaves. In 1867, Truth began working for the American Equal Rights Association, which sought suffrage in New York for women and African Americans. |

|

|

|

|

Return to Top of Page

Selected Quotes on Slavery and Abolition

Quotes appear in chronological order.

Thou shalt not deliver unto his master the servant who has escaped from his master unto thee.

Deuteronomy 23:15

Remember them that are in bonds, as bound with them, and them which suffer adversity, as being yourselves also in the body.

Epistle of Paul to the Hebrews, 13:3

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776, drafted by Thomas Jefferson

Negro slavery is an evil of Colossal magnitude and I am utterly averse to the admission of slavery into the Missouri Territories. It being among my first wishes to see some plan adopted, by which slavery in this country may be abolished by law.

John Adams, founding father, third President of the United States

Slavery is so foreign to the human mind, that the moral faculties, as well as those of the understanding are debased, and rendered torpid by it. All of the vices which are charged upon the negroes in the southern colonies and West Indies… are the genuine offspring of slavery, and serve as an argument to prove they [African Americans] were not intended by Providence for it.

Benjamin Rush, founding father

Who talks most about freedom and equality? Is it not those who hold a bill of Rights in one hand and a whip for affrighted slaves in the other?

Alexander Hamilton, founding father, first Secretary of the Treasury, abolitionist

Freedom is not a gift bestowed upon us by other men, but a right that belongs to us by the laws of God and nature.

Benjamin Franklin, founding father, abolitionist

…Neither my tongue, nor my pen, nor purse shall be wanting to promote the abolition of what to me appears so inconsistent with humanity and Christianity.

Benjamin Franklin, founding father, abolitionist

It is much to be wished that slavery may be abolished. The honor of the States as well as justice and humanity, in my opinion, loudly call upon them to emancipate these unhappy people. To contend for our own liberty, and to deny that blessing to others, involves an inconsistency not to be excused.

John Jay, founding father, first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, abolitionist, in a letter to R. Lushington, March 15, 1786

If the Union must be dissolved, slavery is precisely the question upon which it ought to break.

John Quincy Adams, U.S. Secretary of State, 1820, privately commenting on Missouri Compromise of 1819

[Slavery] is the root of almost all the troubles of the present and the fears for the future.

Former President John Quincy Adams to Alexis de Tocqueville

Americans are so enamored of equality that they would rather be equal in slavery than unequal in freedom… The subjection of individuals will increase among democratic nations, not only in the same proportion as their equality, but in the same proportions as their ignorance.

Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America

I consider involuntary slavery a never-failing fountain of the grossest immorality, and one of the deepest sources of human misery; it hangs like the mantle of night over our republic, and shrouds its rising glories. I sincerely pity the man who tinges his hand in the unhallowed thing that is fraught with the tears, and sweat, and groans, and blood of hapless millions of innocent, unoffending people…

John Rankin, 1823, abolitionist, published in The Castigator, a local newspaper in Ripley, Ohio

If there is no struggle, there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom, and deprecate agitation, are men who want crops without plowing up the ground, they want rain without thunder and lightning.

Frederick Douglass, abolitionist, former slave

It seems incredible that the advocates of liberty should conceive of the idea of selling a fellow creature to slavery.

James Forten, abolitionist, free African American

If you love your children, if you love your country, if you love the God of love, clear your hands from slaves. Burden not your children or country with them.

Richard Allen, abolitionist, former slave, founder of the Bethel African Methodist Church (AME)

Then I will speak upon the ashes.

Sojourner Truth, abolitionist, former slave

Every great dream begins with a dreamer. Always remember, you have within you the strength, the patience, and the passion to reach for the stars to change the world.

Harriet Tubman, abolitionist, former slave

I freed a thousand slaves I could have freed a thousand more if only they knew they were slaves.

Harriet Tubman, abolitionist, former slave

Abolitionists believe that, as all men are born free, so all who are now held as slaves in this country were born free, and that they are slaves now is a sin…

Elijah Parrish Lovejoy, abolitionist who was murdered by pro-slavery mob

I am aware that many object to the severity of my language; but is there not cause for severity? I will be as harsh as truth, and as uncompromising as justice. On this subject, I do not wish to think, or to speak, or write, with moderation. … I am in earnest — I will not equivocate — I will not excuse — I will not retreat a single inch — AND I WILL BE HEARD.

William Lloyd Garrison, abolitionist, January 1, 1831

Enslave the liberty of but one human being and the liberties of the world are put in peril.

William Lloyd Garrison, abolitionist

I will say, finally, that I despair of the republic while slavery exists therein.

William Lloyd Garrison, abolitionist, July 4, 1829

I do not pretend to understand the moral universe; the arc is a long one. My eye reaches but little ways; I cannot calculate the curve and complete the figure by the experience of sight, I can divine it by conscience. And from what I see I am sure it bends towards justice.

Theodore Parker, abolitionist, in speech, “The Present Aspect of Slavery in America and the Immediate Duty of the North,” Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Convention, April 29, 1858

Slavery can only be abolished by raising the character of the people who compose the nation; and that can be done only by showing them a higher one.

Maria Weston Chapman, abolitionist, feminist

Every man knows that slavery is a curse. Whoever denies this, his lips libel his heart.

Theodore Dwight Weld, abolitionist

An immoral law makes it a man’s duty to break it at every hazard.

Ralph Waldo Emmerson, poet, essayist, in speech in 1851 opposing the Fugitive Slave Law

Our fellow country men in chains! – slaves – in a land of light and law! Slaves – crouching on the very plains where rolled the storm of freedom’s war!

John Greenleaf Whittier, abolitionist poet

The law will never make men free; it is men who have got to make the law free. They are the lovers of law and order, who observe the law when the government breaks it.

Henry David Thoreau, in the essay, “Slavery in Massachusetts,” commenting on the Fugitive Slave Law, July 4, 1854

If there breathe on Earth a slave,

Are ye truly free and brave?

If ye do not feel the chain,

When it works a brother’s pain,

Are ye not base slaves indeed,

Slaves unworthy to be freed?

James Russell Lowell, Stanzas on Freedom

These are the woes of slaves;

They glare from the abyss;

They cry, from unknown graves,

We are the witnesses.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, poet

Slavery is a sin against God and a crime against man.

Free Soil Party platform

I John Brown am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land: will never be purged away; but with Blood.

Note written by John Brown, December 2, 1859, the day he was executed

Whenever I hear any one arguing for slavery I feel a strong impulse to see it tried on him personally.

President Abraham Lincoln, in speech to 140th Indiana Regiment, March 17, 1865

As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy. Whatever differs from this, to the extent of this difference, is no democracy.

Abraham Lincoln, 1858

I have always hated slavery, I think as much as any abolitionist.

Abraham Lincoln, July 10, 1858, speech at Chicago, Illinois

I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world.

Abraham Lincoln, October 16, 1854, speech at Peoria, Illinois

Return to Top of Page

|

|

|

|